Roman Roads to Prosperity: Persistence and Non-Persistence of Public Goods Provision

Carl-Johan Dalgaard (University of Copenhagen and CEPR), Nicolai Kaarsen (Danish Economic Council), Ola Olsson (University of Gothenburg) and Pablo Selaya (University of Copenhagen)

Abstract: How persistent is public goods provision in a comparative perspective? We explore the link between infrastructure investments made during antiquity and the presence of infrastructure today, as well as the link between early infrastructure and economic activity both in the past and in the present, across the entire area under dominion of the Roman Empire at the zenith of its geographical extension. We find a remarkable pattern of persistence showing that greater Roman road density goes along with (a) greater modern road density, (b) greater settlement formation in 500 CE, and (c) greater economic activity in 2010. Interestingly, however, the degree of persistence in road density and the link between early road density and contemporary economic development is weakened to the point of insignificance in areas where the use of wheeled vehicles was abandoned from the first millennium CE until the late modern period. Taken at face value, our results suggest that infrastructure may be one important channel through which persistence in comparative development comes about.

URL: http://d.repec.org/n?u=RePEc:cpr:ceprdp:12745&r=his

Distributed by NEP-HIS on: 2018-03-26

Revised by: Martin Söderhäll (Uppsala University)

Summary

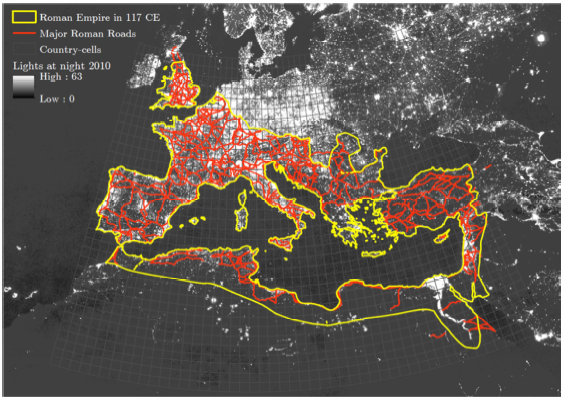

In the paper Roman Roads to Prosperity: Persistence and Non-Persistence of Public Goods Provision the question “How persistent is public goods provision in a comparative perspective?” is examined by estimating the impact of Roman road-density on various proxies for economic activity today (modern roads, night-lights and population density) and in 500 CE (roman settlements). This is done for areas of Europe, the Middle East and Northern Africa covered by Roman roads in 117 CE. The authors argue that the Roman roads “almost presents itself as a natural experiment” since the main purpose of the roads was to simplify military logistics during Roman times. This led to a road network with roads constructed as straight as possible between nodes, especially in newly conquered and undeveloped areas of the Roman Empire.

Figure 1: Roman Roads and Night Lights around Paris

The main findings in the paper are that Roman road density in 117 CE has a statistically significant positive effect on all of the above-mentioned dependent variables, suggesting that the spatial distribution of ancient infrastructure still affects the location of economic activity almost 2000 years later. However, the historical density of ancient infrastructure is not enough to explain the density of modern infrastructure as well as economic activity. The authors hypothesize that persistent use and maintenance of said infrastructure is a necessary condition for the link. To examine the hypotheses the authors’ exploit regional variation in the use of wheeled transport during the first millennia CE. This historical natural experiment is made possible since the Middle East and North Africa abandoned wheeled transport during this period, most probably due to the use of camels, which became a more efficient means of transportation in the region some time during the first millennia (Bulliet 1990).

Figure 2: Roman Roads Network in 117 CE

The developments in the Middle East and North Africa during the first millennia CE led to ancient Roman roads being used to much lesser extent than in Europe were wheeled vehicles (drawn by horses or oxen) continued to dominate among land-based means of transportation up until the nineteenth century. Thus, the authors’ claim, “one should expect influence of Roman roads today only where persistence in infrastructure is found.” In other words, the effect of Roman roads on economic activity today should be insignificant within the Middle East and in North Africa while it should have a positive effect within Europe. However, one should also expect that the density of Roman roads had a positive effect on economic activity in all studied regions before the abandonment of the wheel and the subsequent loss of interest in the use and maintenance of Roman roads in the Middle East and in North Africa.

Figure 3: Relationship between Roman Road Density in 177 CE and Modern Road Density

Econometrically, the hypotheses set by the authors are examined by a cross-sectional specification where the parameter of interest is the influence of Roman road density on various measures of economic activity today and in 500 CE, controlling for (primarily) geographic traits of the grid cells where road density are measured as well as country and language fixed-effects. The empirical results are in line with those hypothesized by the authors. The density of Roman roads had a statistically significant positive effect on economic activity in all specifications except the ones where the modern day variables capturing the degree of economic activity “today” is regressed on Roman road density in the Middle East and North Africa, further strengthening the argument that persistence in infrastructure can explain comparative development over a period of 2000 years.

Comments

The interpretation and implication of the empirical result is quite straightforward. It is clearly a good idea to keep investing in infrastructure as long as the infrastructure has an economic value, something the authors show was the case in Europe but less so in the Middle East and North Africa where the value of Roman infrastructure dropped. At first sight, one potential remark is the large time gap between the cross sections. How would the interpretation of the results look like if the link between Roman roads and economic activity disappeared in large parts of Europe some time during the period 500-2010 CE? Results from previous research (Bosker et. al. 2013; Bosker & Buringj 2017) ease the worry of this question slightly, since they have shown a relationship between Roman road-hubs and city sizes during the period 800-1800. However, it would have been nice to see some specifications for the years between 500 CE and 2010 CE in this paper as well, possibly using city sizes from DeVries (2013) or Bairoch (1991) as a proxy for economic activity. Especially since the scope differs a bit from that in Bosker et. al. (2013) where the estimation (to my knowledge) is done in a panel setting and in Bosker & Buringj (2017) where only Europe is studied.

Aside from that, I have very little to remark on; I find the argumentation against potential threats to internal validity convincing, and find arguments against external validity quite irrelevant due to the exploratory nature of the paper. In a way, the paper can be summarized as both fun and fascinating.

References

Bairoch, P. (1991). Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bosker, M., Buringh, E., & van Zanden, J. L. (2013). “From Baghdad to London: Unraveling Urban Development in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, 800–1800.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 95 (4), 1418-1437.

Bosker, M., & Buringh, E. (2017). “City Seeds: Geography and the Origins of the European City System.” Journal of Urban Economics 98, 139-157.

Bulliet, R. W. (1990). The Camel and the Wheel. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

De Vries, J. (2013). European Urbanization, 1500-1800. London: Routledge.