Capital Shares and Income Inequality: Evidence from the Long Run

by Erik Bengtsson (Lund) and Daniel Waldenström (Paris School of Economics and CEPR)

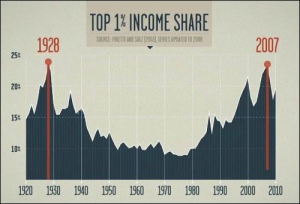

Abstract – This article studies the long-run relationship between the capital share in national income and top personal income shares. Using a newly constructed historical cross-country database on capital shares and top income data, we find evidence on a strong, positive link that has grown stronger over the past century. The connection is stronger in Anglo-Saxon countries, in the very top of the distribution, when top capital incomes predominate, when using distributed top national income shares, and when considering gross of depreciation capital shares. Out of-sample predictions of top shares using capital shares indicates several cases of over- or underestimation.

Freely available for a limited time at: The Journal of Economic History, 78(3): 712-743

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050718000347

Review by Leandro Prados de la Escosura (Universidad Carlos III, Groningen, and CEPR)

Until recently, many academic economists would react sceptically to the idea of income inequality. It is absolute poverty what matters, they would argue, and sustained growth is the answer. It would be misled, however, to conclude the only lately has inequality become part of the economists’ agenda. Actually inequality has always been present in economists’ preoccupations. Its symptoms have varied, as social sensitivity to inequality has changed over time. Classical economists identified personal income distribution with the functional income distribution as inequality largely depended on the gap between average incomes of capital and labour. This is clearly exposed in David Ricardo’s famous passage in which he noted that the explaining the distribution of “the produce of earth (…) among (…) the proprietor of the land, the owner of the stock or capital (…) and the labourers” is the main purpose of political economy. In the early 20th century, as the share of skilled workers in the labour force was increasing, Simon Kuznets noted the dispersion of labour incomes and highlighted its role as a driving force of income inequality. At the turn of the century, the increase in the concentration of income at the top of the distribution has renewed the concern about inequality as the contributions of the late Sir Tony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and their collaborators evidence. It is in this context where Eric Bengtsson and Daniel Waldeström’s important contribution should be read.

The purpose of Bengtsson and Waldeström was to the test the existence of a long run connection between the functional and the personal distribution of income. As economic historians they find no reason to assume the relationship would be stable over time and across countries since many other dimensions (technology, institutions, personal incomes composition, …) will impinge on it.

Their analytical framework is the decomposition of income inequality, using the coefficient of variation, into wages and capital income dispersion, factor shares, and the correlation between capital and labour income, from which a link between capital share and income inequality is predicated. More specifically, a positive association between the two metrics is hypothesised: as capital returns are more unevenly distributed than those accruing to labour, a rise in the share of capital in national income would result in an increase in personal income inequality.

Once their hypothesis is defined, they deal with the data. On the basis of capital returns and GDP, mostly derived from previous scholarly work, they put together a reasonably homogeneous dataset on capital shares, that is, the ratio of capital incomes (interest, profits, dividends, and realized capital gains) to national income for 21 countries (mostly present-day OECD countries) since 1900. Capital returns are computed form the income side of historical national accounts, which raises the challenge of how to distribute mixed incomes (those of self-employed) between capital and labour. The so called labour method that attributed to the self-employed a labour income equal to that of the average employee in each specific sector of economic activity is the usual approach. Then, they choose income concentration at the top of the distribution as a measure of personal income distribution, since alternative metrics such as the Gini coefficient are not available on yearly basis for their country sample and time span. The dataset on the share of income accruing to the 10, 1, and 0.1 top per cent derives from the World Inequality Database (https://wid.world/wid-world/).

The approach to test the association between personal and functional income distribution is panel regression analysis, in which a log-linear relationship is predicated between top income shares, as dependent variable, and the net (gross) capital share, so the latter’s parameter represents the elasticity of income concentration (inequality) with respect to the capital share. In addition to the baseline equation, they also compute more complex models which include control variables (level of development, proxied by GDP per head; structural change, by the agricultural labour share; relevance of private capital by stock marker capitalisation; and size of the public sector, by the government spending to GDP ratio) country fixed effects, and a linear time trend. The overall view of all countries over the 20th century is complemented by a breakdown by epoch (pre World War II, 1950-80, and 1980-2015) and type of countries (three clubs, the Anglo-Saxon, the Scandinavian, the Western European).

Their main finding is a robust association between top income shares and capital shares over the long run, that results in a high elasticity of income inequality with respect to the capital share that declines when specific periods (1950-1980 and 1980-2015) are considered. Thus, a 10 per cent rise in the net capital share is corresponded by an almost similar increase in income concentration at the top. It is worth noting, however, the lower elasticity –and statistical significance- found for the pre-World War II era. When more complex models, including covariates, are used the fit of the regressions increases but reduces the coefficient for the capital share that, nonetheless, still holds up. The association becomes stronger as top incomes shares are restricted to the 0.1 per cent and a possible explanation is that these mainly correspond to capital earners.

The authors also explore the extent to which capital incomes at the top of the distribution account for the association between top income shares and the capital share. They confirm previous findings suggesting that capital incomes predominate in the incomes of the top earners and increase within the income top. However, the authors find that high-paid salaried employees have been replacing capital earners at the very top of the distribution. In any case, the association between top income share and the capital share is stronger when capital rather than wage or total top incomes are considered.

1913: The wealthy man profits from the sweat of the worker. The cartoon is titled ‘The Reflection’ and the capitalist exclaims ‘I’m a self-made man, look at me’. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The paper concludes with the authors addressing the crux of the matter, is the capital share a good predictor of inequality? In order to do it, they re-run panel regressions leaving aside the country whose inequality is to be predicted. The results are positive in general, but the authors acknowledge that capital shares are not perfect predictors of concentration at the top of the distribution, to which one may add that top income shares are neither a precise measure of personal income inequality.

This thought-provoking paper raises some reflections. Would not it more intuitive the framework proposed by Milanovic (2005) than the authors’ breakdown of the coefficient of variation? Milanovic decomposes inequality into between-group and within-group inequality. In a similar scenario, with only two groups: proprietors, to whom capital (and land) incomes accrue, and workers who receive the returns to labour, personal income inequality results from both the gap between average incomes of capital and labour (that is, a metric that captures the functional distribution of income) and the dispersion of incomes within both capital owners and workers.

A reference to top income shares shortcomings is missing. Uncritically assuming it is a good proxy of personal income distribution neglects that fact that although top income share satisfies axioms of income scale independence, principle of population, and anonymity only weakly does the Pigou-Dalton transfer principle. Moreover, it is silent on how inequality evolves at the bottom of the distribution.

Some of the results could have been explored more. For example, their finding of a lower elasticity of income inequality with respect to the capital share in the pre-World War II era (that is also found when the Ginis is used as dependent variable) deserves further examination. On the one hand, it seems at odds with the inference of a much higher association between income inequality and the capital share in earlier phases of economic development, as between-group inequality (the average capital incomes to labour incomes ratio) has a larger weight in total personal inequality (the dispersion of capital and labour incomes is presumably lower). On the other, a potential explanation would be the increasing dispersion of factor returns –wages, in particular- in the early 20th century, a finding consistent with Kuznets’ focus on the rise of skilled labour and rural-urban migration.

Another neglected issue (somehow a paradox given the authors’ background) is why income concentration at the top and the net capital share are not associated in the Nordic countries since 1980.

The avenues for research the paper opens deserved more detailed consideration. It is true that in the last section the authors address the issue of how good a prediction of personal inequality the capital share is. However, an obvious extension would be to use the capital share as a proxy for income inequality prior to the early 20th century, when hardly any data on top income shares are available and other measures of inequality such as the Gini are rare.

The paper is worth reading as it represents an ambitious and successful project to deal with income inequality over space and time. Moreover, a most valuable online appendix that complements the freely accessible dataset provided by the authors’ webpage accompanies the paper.

References

Milanovic, B. (2005), Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality, Princeton: Princeton University Press.